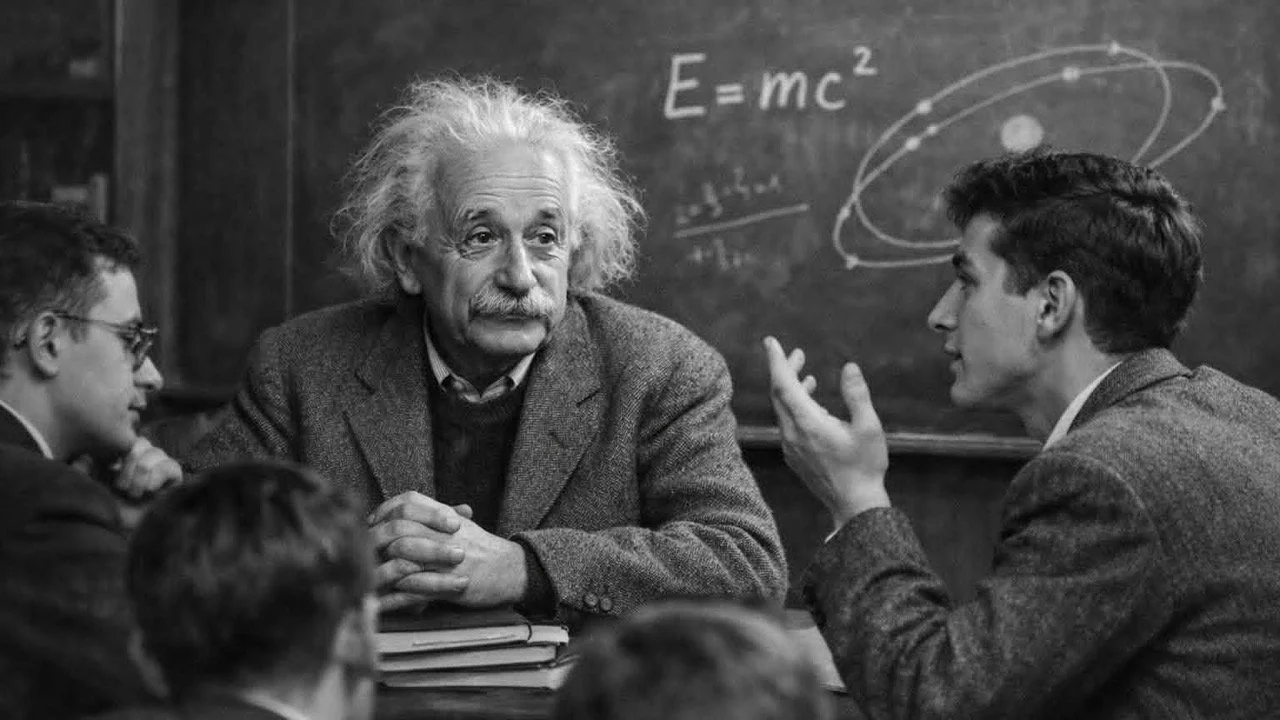

One of Einstein’s students once asked him what logic really means.

Einstein replied that he would answer with a question.

He asked the student to imagine two workers entering a chimney to clean it. When they come out, one has a dirty face and the other a clean face. Einstein then asked which of them would go and wash their face.

The student answered immediately that the worker with the dirty face would wash.

Einstein said this was incorrect. The worker with the clean face would be the one to wash, because he would look at his colleague, see the dirt, and assume his own face must be the same. The worker with the dirty face, seeing a clean face, would assume he was clean as well.

The student agreed and said this was logical.

Einstein disagreed. He pointed out that the question itself was flawed. Two people entering the same chimney at the same time would not emerge with one clean and one dirty face. The scenario violated basic logic before the reasoning even began.

The point is simple. Sometimes logic fails not because of a poor answer, but because the question itself is wrong. I think the moral of the story is when that happens, no amount of clever reasoning will lead to the right conclusion.